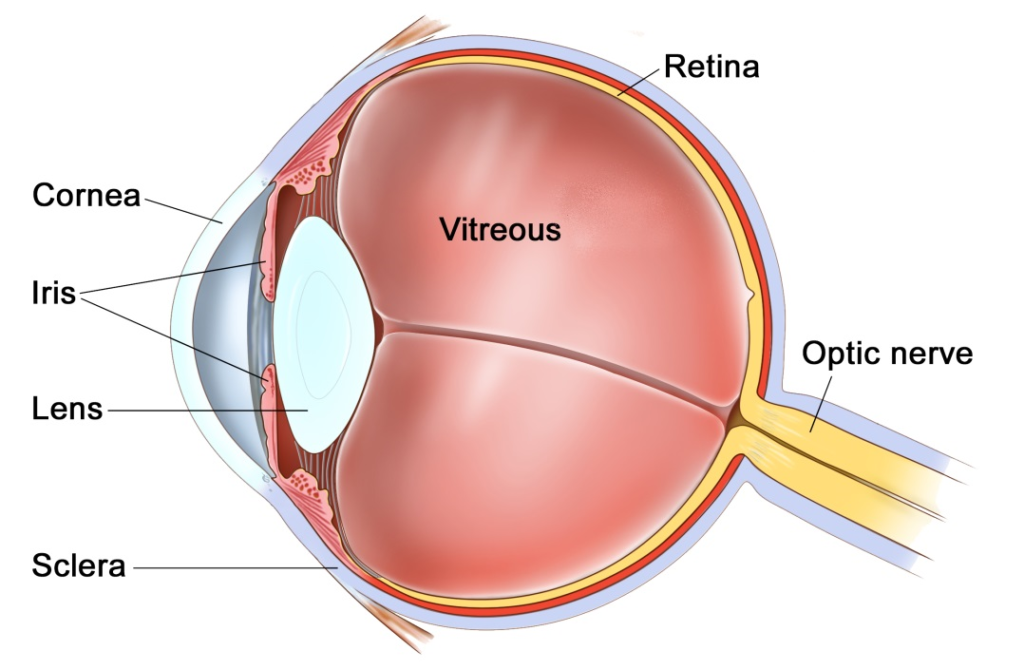

The eye

The eye is like a camera, with a lens at the front to focus light, and a film at the back to capture an image. The photographic film of the eye is known as the retina. In between the lens and the retina, the eye is filled with a gel, known as vitreous.

The vitreous gel was important during development of the eye where it acted as a scaffold for blood vessels. After birth the gel is no longer required and gradually liquefies and shrinks in size. Inevitably, usually after 40 years or more, the gel has shrunk so much that it can no longer completely fill the cavity of the eye. At this point the vitreous gel separates from the retina in a process known as a ‘posterior vitreous detachment’ or ‘PVD’. This is a natural process and occurs in everybody with time.

As with many conditions, this natural process can occasionally go wrong resulting in a range of medical conditions, such as floaters, vitreous haemorrhage, detached retina, epiretinal membrane, or macular hole. These conditions alter the focus of light entering the eye and cause blurred vision.

What are floaters?

Floaters are small, mobile, translucent shadows that whizz across our vision. They are often described as a ‘cobweb’ or ‘amoeba’. When we are young, these floaters are actual debris within the vitreous gel of the eye. As we age the gel pulls away from the retina, during a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), and the back surface of the gel also becomes visible as floaters. The PVD floaters tend to be bigger and more persistent than other floaters. One particular floater, known as a ‘Weiss ring’ is where the posterior vitreous used to insert around the optic nerve.

Over the years floaters tend to come and go. If you ignore them then the brain begins to notice them less also, but they never fully disappear. If you look for floaters or move the eye around you will always be able to find them.

An example of how floaters can appear

Are floaters always harmless?

In the vast majority of people, the vitreous gel peels away from the back of the eye without causing any harm. In a small percentage of people, as the gel peels away, if the gel is too adherent at any one point, it may tear a blood vessel or the retina. The sign of this happening is a sudden and dramatic change in the floaters. This is commonly known as a sudden ‘shower of floaters’. If you experience this sudden change, then you should go to an eye casualty urgently to have your retina examined. If the retina has torn, then prompt laser treatment in the outpatient clinic will prevent any problem. If a retinal tear is not sealed quickly with laser, then the entire retina may start to peel away from the back of the eye, known as a detached retina. The sign of a detached retina is a curtain-like shadow coming over the eye. If this blurred shadow gets to the central vision then you will have lost some vision permanently. When the retina has started to detach, the only way to reattach the retina is with a vitrectomy operation.

Can floaters be removed?

Although floaters can be very annoying, they are completely harmless. For this reason, if you can learn to ignore them it is best to leave them alone. However, if they are very intrusive and interfere with critical tasks such as reading, working or driving, then they can be removed with an operation called a vitrectomy.

What does a vitrectomy involve?

A vitrectomy is a surgical procedure that removes the vitreous gel from the eye to clear the vision. The operation is very much like modern day case cataract surgery. It is usually performed whilst you are awake as a day case procedure, although if you would prefer the procedure can be done with sedation or a general anaesthetic. It takes about 20-30 minutes. Three pinpricks less than 0.5mm in diameter are made at the front white part of the eye (sclera) and the gel is removed through these. The eye has a pad for one night, and the vision takes 1-2 days to improve back to normal. You have eye drops for 4 weeks afterwards.

Are there any risks?

All procedures carry some degree of risk. If you have not had cataract surgery, then all patients within 1-2 years of surgery will develop a cataract. Cataracts are a cloudy lens in the eye that blurs the vision and cannot be corrected with glasses. Cataracts are a normal natural part of aging, and most people will require cataract surgery in their lifetime anyway. The lens can be removed at the time of the vitrectomy to prevent it becoming cataractous, or the cataract can be removed separately when it develops.

About 1 in 20 people may require a temporary gas bubble in the eye after surgery. This is of little consequence except it means that you cannot see clearly or fly for about 3 weeks. About 1 in 100 patients can develop a detached retina, where the lining of the eye peels away. This would require an operation to fix, but can affect the vision if it is not caught early enough. About 1 in 1000 patients can develop an infection or some bleeding in the lining of the eye. Both of these conditions can blind the eye.

Where can I find more information?

www.nei.nih.gov/health/floaters/index.asp

www.moorfields.nhs.uk/Eyehealth/Commoneyeconditions/Floaters

www.nhs.uk/conditions/Floaters/Pages/Introduction.aspx

www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floaters

Important information

After your operation your sight should gradually improve and the eye feel more comfortable. If at any stage during your recovery you feel that the eye is becoming more painful, or the sight worse, then you must call for advice. Do not wait for your appointment.

Useful Telephone Numbers

Mr Steven Harsum’s Private Secretary 0207 112 8246

St Helier Eye Day Case Unit 020 8 296 3524

Ashtead Hospital 01372 221 400

St Anthony’s Hospital 0208 337 6691

Emergencies:

Monday to Friday – St Helier Eye Casualty: 0208 296 3817

Evening/Weekend – Moorfields at St Georges: 020 8725 2064